Peer-Reviewed Exhibits content in SiRO is protected by a Creative Commons License.

Silences in the Historical Record of Reproductive Freedom in America

40

|

Women of color’s struggle for birth control represents a complicated tangle of social, political, and religious factors. Contemporary activism led by WOC have adopted the term reproductive justice in order "to recognize that the control, regulation, and stigmatization of female fertility, bodies, and sexualities are connected to the regulation of communities that are themselves based on race, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality.”@Jael Miriam Silliman, et al.,Undivided Rights: Women of Color Organize for Reproductive Justice. (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004). Unfortunately, the mainstream historical narrative of reproductive rights in America generally misses this complexity.

|

The radical mobilization of birth control among WOC began in slavery through subversive efforts to prevent forced breeding. As Dorothy Roberts points out, reproduction played a central role in slavery as it enabled the growth of slave populations@Dorothy E. Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Vintage Books, 1999).. During this time, African-American women actively resisted slavery through birth control measures that arose from African folk knowledge of contraceptives and abortifacients@Ross, Loretta J. "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History." Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 3, no. 2 (1992): 274-284

Ross, Loretta J. "African-American Women and Abortion." Abortion Wars: A Half Century of Struggle, 1950–2000, ed. Rickie Solinger (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998).. Later, The Colored Women’s Club Movement, spearheaded by the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC), led various advocacy efforts.@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History."

Lerner, Gerda. “Early Community Work of Black Club Women.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 59, no. 2, 1974, pp. 158–167. The Club Movement spoke out against racially-motivated sterilization programs, hosted lectures on birth control, established crucial networks for disseminating information about birth control among African-American women, and sought the establishment of family planning clinics in black communities.@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion."

Ross, Loretta J. "African-American Women and Abortion." Abortion Wars: A Half Century of Struggle, 1950–2000, ed. Rickie Solinger (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998).. Later, The Colored Women’s Club Movement, spearheaded by the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC), led various advocacy efforts.@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History."

Lerner, Gerda. “Early Community Work of Black Club Women.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 59, no. 2, 1974, pp. 158–167. The Club Movement spoke out against racially-motivated sterilization programs, hosted lectures on birth control, established crucial networks for disseminating information about birth control among African-American women, and sought the establishment of family planning clinics in black communities.@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion."

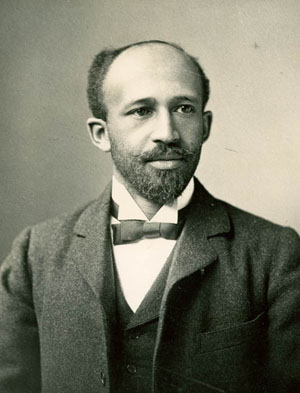

In the early 20th century, the debate over birth control within the African American community evinced broader discussions of the future of the black race in America. Many prominent black minds argued that birth control and abortion programs amount to race- and class-based genocide. Black Nationalists like Marcus Garvey believed that racial oppression demanded increases in the black population and that birth control stifled such efforts through “race suicide."@Roberts, Dorothy. "Black Women and the Pill." Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 32, no. 2, 2000, pp. 92-93. Others, like scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, advocated for reproductive freedom and participated in broader birth control efforts of the early 20th century@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History.". Du Bois, like his contemporaries in the birth control movement at that time, argued for "quality and not mere quantity."

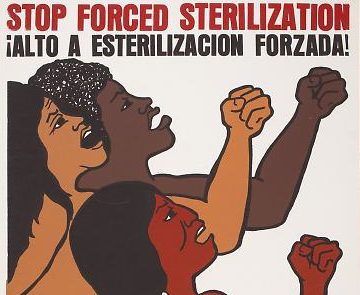

Forced sterilization of African-Americans beginning in the early 20th century legitimized fears of racial genocide. Forced sterilization continued well into the latter half of the 20th century, often funded by the government and occurring without women's knowledge or consent.@Loretta J. Ross, “A Simple Human Right; The History Of Black Women And Abortion

,” On the Issues Magazine, 1994, available from http://www.ontheissuesmagazine.com/1994spring/spring1994_Ross.php Such programs engendered an enduring suspicion among POC of self-regulated birth control via the pill and other measures: “many blacks saw the pill as just another tool in the white man’s efforts to curtail the black population.”@Roberts, “Black Women and the Pill,” 93. Yet, as Silliman and colleagues note, "women of color have had no trouble distinguishing between population control—externally imposed fertility control policies—and voluntary birth control—women making their own decisions about fertility.”@Jael Miriam Silliman, et al., Undivided Rights: Women of Color Organize for Reproductive Justice. (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004), 7. Ross exemplifies this point, writing that black feminists during the civil rights movement countered arguments about race suicide by highlighting the role of birth control and abortion in revolutionary action: "black liberation in any sense could not be won without women controlling their lives. The birth control pill, in and of itself, could not liberate African-American women, but it 'gives her the time to fight for liberation in those other areas."@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History," 283.

In 1969, the head of the Black Women’s Liberation Committee of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Francis Beal, spoke out in favor of black women's right to decide when to have children.@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History," 282. In 1970, Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman in Congress, firmly stated: "To label family planning and legal abortion programs 'genocide' is male rhetoric, for male ears. It falls flat to female listeners and to thoughtful male ones." Under the leadership of Dr. Dorothy Heights, the National Council of Negro Women became the first black women's organization to publicly support the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973.@Loretta Ross, “Dr. Dorothy Height, A Sister Whose Shoulders We Stand On,”http://msmagazine.com/blog/2010/04/21/dr-dorothy-height-a-sister-whose-shoulders-we-stand-on/. Echoes of the competing concerns of population control and voluntary motherhood endure into the present and collide with many other factors surrounding the issue of birth control in communities of color. As Dorothy Roberts summarizes,

“For black women, the politics of the pill doesn’t fall into a simple liberal-conservative dichotomy. The meaning of birth control is complicated by the racist denigration of black childbearing, including deliberate campaigns to limit black fertility; sexist and religious norms with the black community; and many white feminists’ ignorance about the unique issues facing black women. Black women’s attitudes about the pill are shaped by a broader social context that includes racial injustice as well as gender inequality and religious traditions."@Dorothy Roberts. “Black Women and the Pill,” 92.

,” On the Issues Magazine, 1994, available from http://www.ontheissuesmagazine.com/1994spring/spring1994_Ross.php Such programs engendered an enduring suspicion among POC of self-regulated birth control via the pill and other measures: “many blacks saw the pill as just another tool in the white man’s efforts to curtail the black population.”@Roberts, “Black Women and the Pill,” 93. Yet, as Silliman and colleagues note, "women of color have had no trouble distinguishing between population control—externally imposed fertility control policies—and voluntary birth control—women making their own decisions about fertility.”@Jael Miriam Silliman, et al., Undivided Rights: Women of Color Organize for Reproductive Justice. (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2004), 7. Ross exemplifies this point, writing that black feminists during the civil rights movement countered arguments about race suicide by highlighting the role of birth control and abortion in revolutionary action: "black liberation in any sense could not be won without women controlling their lives. The birth control pill, in and of itself, could not liberate African-American women, but it 'gives her the time to fight for liberation in those other areas."@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History," 283.

In 1969, the head of the Black Women’s Liberation Committee of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Francis Beal, spoke out in favor of black women's right to decide when to have children.@Ross, "African-American Women and Abortion: A Neglected History," 282. In 1970, Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman in Congress, firmly stated: "To label family planning and legal abortion programs 'genocide' is male rhetoric, for male ears. It falls flat to female listeners and to thoughtful male ones." Under the leadership of Dr. Dorothy Heights, the National Council of Negro Women became the first black women's organization to publicly support the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973.@Loretta Ross, “Dr. Dorothy Height, A Sister Whose Shoulders We Stand On,”http://msmagazine.com/blog/2010/04/21/dr-dorothy-height-a-sister-whose-shoulders-we-stand-on/. Echoes of the competing concerns of population control and voluntary motherhood endure into the present and collide with many other factors surrounding the issue of birth control in communities of color. As Dorothy Roberts summarizes,

“For black women, the politics of the pill doesn’t fall into a simple liberal-conservative dichotomy. The meaning of birth control is complicated by the racist denigration of black childbearing, including deliberate campaigns to limit black fertility; sexist and religious norms with the black community; and many white feminists’ ignorance about the unique issues facing black women. Black women’s attitudes about the pill are shaped by a broader social context that includes racial injustice as well as gender inequality and religious traditions."@Dorothy Roberts. “Black Women and the Pill,” 92.

As Roberts hints, the mainstream narrative of birth control activism presently paints a fairly simplistic picture of dichotomous perspectives, which fails to capture more nuanced perspectives among Black women. The mainstream narrative also fails to recognize the problematic roots of the contemporary reproductive rights movement. This narrative typically begins with Margaret Sanger, whose radical acts in the early 20th century laid the foundation for generations of activists. In what follows, I introduce Margaret Sanger before discussing how her work has been understood in light of her alignment with the eugenics movement.

|

Margaret Sanger was an early birth control advocate and sex educator in the U.S., as well as the founder of the international family planning movement. Most notably, her work led to the founding of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and to the social and legal the acknowledgement of women’s reproductive rights. Her work resulted in physicians’ right to distribute contraceptive information and to prescribe and distribute contraceptives. Her persistent efforts to secure funding for contraceptive research led to the development of various forms of birth control, including the birth control pill. Sanger also advocated for comprehensive sex education. Beginning in 1912, she wrote a sex column in the New York Call entitled “What Every Girl Should Know.”

|

Through her work and writings, Sanger assumed a radical position. Summing up this position, in 1914 Sanger explained the title of her periodical, The Woman Rebel, writing:

"Because I believe that deep down in woman's nature lies slumbering the spirit of revolt.

Because I believe that woman is enslaved by the world machine, by sex conventions, by motherhood and its present necessary child-rearing, by wage-slavery, by middle-class morality, by customs, laws and superstitions.

Because I believe that woman's freedom depends upon awakening that spirit of revolt within her against these things which enslave her.”@Margaret Sanger, "WHY THE WOMAN REBEL?" The Woman Rebel, 1, no.1 (March 1914): 7.

"Because I believe that deep down in woman's nature lies slumbering the spirit of revolt.

Because I believe that woman is enslaved by the world machine, by sex conventions, by motherhood and its present necessary child-rearing, by wage-slavery, by middle-class morality, by customs, laws and superstitions.

Because I believe that woman's freedom depends upon awakening that spirit of revolt within her against these things which enslave her.”@Margaret Sanger, "WHY THE WOMAN REBEL?" The Woman Rebel, 1, no.1 (March 1914): 7.

|

Sanger embraced these principles as she engaged in civil disobedience, pursuing initiatives that tested or outright transgressed the boundaries of the law. In her first foray with the law, Sanger published and disseminated the aforementioned The Woman Rebel, a birth control periodical, in violation of the Comstock Laws. Passed in 1873, the Comstock Laws prohibited the mailing of indecent materials, including those “intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion."@Act of March 3, 1873, ch. 258, 2 Stat., 599. Retrieved fromhttps://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=002/llsl002.db&recNum=41 When the postal service preempted dissemination of the first issue of The Woman Rebel for violating the law, Sanger declared a month later in issue number two: “The Woman Rebel feels proud the Post Office authorities did not approve of her. She shall blush with shame if even she be approved by officialism of 'Comstockism.'”@Baskin, Alex. Woman Rebel. Archives of Social History, 1976. Continuing to publish and disseminate The Woman Rebel, Sanger was soon arrested and charged with violating nine counts of violating the Comstock laws. Without an attorney and otherwise being unprepared for her day in court, Sanger requested a postponement to prepare her case. When the judge did not grant her request, Sanger fled to Canada and then England rather than risk jail time and remained abroad until she felt sufficiently prepared for court. In transit to England, Sanger ordered the release of 100,000 pamphlets, entitled "Family Limitation," on contraception. Shortly after Sanger returned to the U.S. to face her trial, her young daughter died of pneumonia. Through effective campaigning, compounded by the tragedy of her daughter’s death, Sanger drew overwhelming public support and her case was dropped. While the case did not prompt an amending of the law, it resulted in more open discussions of birth control and Sanger and her cause gained greater visibility.@Fawcett, James Waldo. Jailed for Birth Control: the Trial of William Sanger, September 10, 1915. [New York: The Birth Control Review], 1917.

|

The same year that charges were dropped, in 1916, Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in American in Brownsville in Brooklyn, NY. Nearly 150 women greeted Sanger and her associates upon the clinic’s grand opening.@Sullivan, Taylor, “One Hundredth Anniversary of the Brownsville Clinic—A MediaOpportunity ,”Margaret Sanger Papers Project , October 14, 2016, available from https://sangerpapers.wordpress.com/tag/brownsville-clinic/ Ten days after the opening, Sanger, her sister Ethel Byrne, and Fania Mindell, were arrested. Byrne was tried first and sentenced to 30 days in a workhouse, during which she went on a hunger strike that brought her near to death. Byrne’s hunger strike garnered media coverage and eventually public sympathy for Sanger’s case. During her trial, Sanger defiantly insisted: “I cannot respect that law as it stands today,” which resulted in her receiving the same sentence as her sister.@Sanger, Margaret, and Alex Baskin. Woman Rebel. (New York: Archives of Social History, 1976.)

|

In spite of Sanger’s vast strides in advancing women’s reproductive freedom, it must also be recognized that her work grew out of association and alliance with eugenicists. In fact, some have argued that this alignment helped the birth control movement survive and thrive, particularly as it strengthened their legitimacy and position in the face of opposition from doctors and the Catholic Church.@Ordover, Nancy. American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). Eugenics featured prominently in her speeches and writings, particularly in the periodical the Birth Control Review, where nearly every issue included some piece related to eugenics.@Weingarten, Karen. “The Inadvertent Alliance of Anthony Comstock and Margaret Sanger: Abortion, Freedom, and Class in Modern America.” Feminist Formations, vol. 22, no. 2, 2010, pp. 42–59. Yet, Sanger’s involvement with eugenics remains contentious for many. It is clear that Sanger’s vision of eugenics diverged somewhat from the mainstream vision and that she often pushed back on these points of disagreement. For example, Sanger believed in and advocated for women’s autonomy, which she sometimes viewed as being threatened by eugenicists’ belief in a top-down, paternalistic control of populations.@Ordover. Sanger also occasionally acknowledged inherent class-biases within the movement@Alexander Sanger. “Eugenics, Race, and Margaret Sanger Revisited: Reproductive Freedom for All?” Hypatia, vol. 22, no. 2, 2007, pp. 210–217. and to some extent rejected “race control." Still, Sanger advocated for policies with racist, ableist, and classist implications. For example, Sanger supported the control of poor and disabled populations via birth control and even forced sterilization. She believed those deemed “unfit” procreated at higher rates than those deemed “fit” and, thus, concluded:

"[T]he example of the inferior classes, the fertility of the feeble-minded, the mentally defective, the poverty-stricken classes, should not be held up for emulation to the mentally and physically fit though less fertile parents of the educated and well-to-do classes. On the contrary, the most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the overfertility of the mentally and physically defective.'”@Ordover. |

|

With this statement, Sanger argues that, rather than increasing procreation among those deemed “fit,” eugenicists and birth controllists should focus on limiting procreation among those deemed “unfit.” While Sanger may not have explicitly expressed prejudices, her actions and statements reveal shameful implicit biases. As Nancy Ordover explains:

"Sanger cannot elude the designation of eugenicist simply because there is no recorded evidence of her uttering blunt statements linking specific ethnic groups to economic, social, or intellectual shortcomings. Several of her campaigns, both in the United States and abroad, were intentionally race-specific. Furthermore, even a cursory glance at who constituted the urban and rural poor who fell prey to the convergence of birth control and scientific racism reveals that her work was clearly informed by ethnic/racial preoccupations having more to do with eugenics practices than reproductive rights."@Ordover. |

|

Dorothy Roberts (and many others) have more explicitly condemned Sanger, emphasizing the long-lasting ramifications of her alliance with eugenics on the broader struggle for reproductive freedom:

"Although its most prominent figure, she did not single-handedly create the political forces that shaped the meaning of birth control. But Sanger’s shifting alliances reveal how the prevailing racial order in influenced the meaning of reproductive freedom—whether reproductive technologies were used for women’s emancipation or their oppression. As the movement veered from its radical, feminist origins toward a eugenic agenda, birth control became a tool to regulate the poor, immigrants, and black Americans."@Roberts, Dorothy. "Margaret Sanger and the racial origins of the birth control movement." Racially writing the republic: Racists, Race Rebels, and Transformations of American Identity, edited by Bruce Baum and Duchess Harris,196-213 (New Haven: Duke University Press, 2009). |

Even when radical figures resist some of the hegemonic ideals of their present, they often still maintain others. Sanger’s problematic views serve as a reminder that Sanger ultimately represented a privileged class and that narratives of history often omit the contributions of marginalized communities and distort events to create a “cleaner” story. In describing the production of history, Michel-Rolph Trouillot distinguishes between the “what happened” and “that which is said to have happened.”@Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015) 2. Trouillot elaborates:

“history reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of production of such narratives. Only a focus on that process can uncover the ways in which the two sides of historicity intertwine in a particular context. Only through that overlap can we discover the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others.”@Trouillot, 25.

We can see silences enter into the historical record initially in sources, in what enters into archives, how historical narratives are constructed, and how we assign significance to events and narratives.@Trouillot. In the case of birth control activism, prominent historical narratives elide the “blemishes” of slavery, eugenics, and systemic racism. This is evidenced, for example, in the relatively robust material archive and myth-making surrounding Margaret Sanger, compared with the relative dearth of archival materials related to reproductive activism among women of color. Some silences can be minimized post hoc, and some cannot. For this reason, it is important to maintain a critical eye in both the preservation and assembling of historical artifacts.

“history reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of production of such narratives. Only a focus on that process can uncover the ways in which the two sides of historicity intertwine in a particular context. Only through that overlap can we discover the differential exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others.”@Trouillot, 25.

We can see silences enter into the historical record initially in sources, in what enters into archives, how historical narratives are constructed, and how we assign significance to events and narratives.@Trouillot. In the case of birth control activism, prominent historical narratives elide the “blemishes” of slavery, eugenics, and systemic racism. This is evidenced, for example, in the relatively robust material archive and myth-making surrounding Margaret Sanger, compared with the relative dearth of archival materials related to reproductive activism among women of color. Some silences can be minimized post hoc, and some cannot. For this reason, it is important to maintain a critical eye in both the preservation and assembling of historical artifacts.